Chapter Two: Planning for Sanitation Projects

Contents

1 Chapter Two: Planning for Sanitation Projects

1.1 2.1 INTRODUCTION

Safe sanitation and good hygiene practices are fundamental to human development and well-being (WHO/UNICEF, 2015).These practices are also fundamental in ensuring the achievement of adequate nutrition, gender equality, education and the eradication of poverty (WHO/UNICEF, 2015). It is estimated that for every US $1 invested in sanitation, there is a return of US$5.50 in lowering health care costs, promoting productivity and actualizing fewer premature deaths (National Bureau of Statistics, 2014). In Tanzania, unplanned settlements increase has intensified the challenge of access to sanitation and hygiene services to urban dwellers. It is estimated that only 34.2% of the urban population has access to improved sanitation and the remaining use basic sanitation facilities or practice open defecation (National Bureau of Statistics, 2014).

The planning for the sanitation services delivery is undertaken alongside urban and town master planning processes, under the auspices of the Ministry of Lands, Housing and Human Settlements Development (MLHHSD). The process is highly centralized and often resorts to recommending the centralized sanitation service chain. The process is not context specific and in most cases the master plans are not informed by research or understanding of the local sanitation status. The demand for sanitation is not assessed and there is little, or no communication between the planners and intended future users. Consequently, social, gender, cultural and religious aspects are not sufficiently considered when designing sanitation projects. In other cases, environmental factors are not considered in the design, which sometimes leads to the unsafe situations. For example, in low-income urban areas where pit emptying is often a necessity, such sanitation services are often lacking or too expensive. Hygiene education to improve sanitation behaviour of the community is rarely included in sanitation projects because community education and sanitation projects have different implementation perspectives and time-scales.

In the light of the above background, this design manual is intended to provide the planning framework that will assist in the selection of sanitation systems that are appropriate and sustainable for various local contexts in Tanzania.

1.2 2.2 PLANNING STAGES AND PROCESSES

The planning processes and stages which can lead to the selection of the most appropriate, effective and sustainable sanitation systems are discussed in the next section.

1.2.1 2.2.1 Community Mobilization and Sensitization Campaigns

The first step is for the community to request improved sanitation services. This can be through community mobilization and sensitization campaigns to create demand for sanitation services. Community mobilization is presumed to be undertaken by the CBWSO leadership in collaboration with the Local Government and village leaderships. At times a trained community moderator can be sought from the MoW or RUWASA to facilitate the campaigns. The manner of the mobilization is through formal village or area meetings. Once a demand for improved sanitation facilities has been expressed, technology selection should be preceded by or based upon a participatory needs assessment. Hygiene awareness and promotion campaigns can increase demand for improved sanitation facilities. Site visits by the community representatives led by CBWSO can assist in the technology choice process.

1.2.2 2.2.2 Analysis of the Existing Sanitation Situation

This is the stage of planning where the sanitation situation at hand will be

analysed and assessed. Situation analysis is undertaken through a participatory

assessment involving a targeted community. A participatory assessment should

be carried out to determine if there are problems related to:

(a) existing human excreta-disposal system;

(b) hygiene and defecation behaviour (among men, women and children);

(c) the overall hygienic environment and

(d) prevalence of human excreta-related diseases.

Also necessary are:

(a) a participatory assessment of the cultural, social and religious factors that

may influence the choice of befitting sanitation technology;

(b) a participatory assessment of the local conditions,

(c) capacities and resources (material, human and financial);

(d) community ability and willingness to pay,

(e) the identification of local preferences for sanitation facilities, and

(f) possible variations.

1.2.3 2.2.3 Synthesis

Data should be collected relating to all the factors that can influence the

performance of sanitation systems. Several criteria can help in the analysis of

the data and in choosing the design of the appropriate sanitation system:

(a) Match user preferences according to local capacities and environmental

conditions, such as the possibility of a risk of contaminating water sources.

The preferences of all sanitation users should be considered, including men,

women, children and disabled people.

(b) Match investment requirements to the costs of the relevant technology and

community’s ability/willingness to pay.

(c) Match community needs to the availability of materials.

(d) Match the proposed design options to the availability of craftsmanship.

(e) Match O&M requirements to the prevailing sanitation behaviour and to local

capacities.

(f) Identify promotional campaigns, micro-credit mechanisms and hygiene

education programmes that could accompany the technology selection and

installation process.

1.2.4 2.2.4 Discussions with the Target Communities

Discussions should be held with the relevant community about sanitation options. These should include discussions about the technical, environmental, financial and hygiene implications of each option. The discussion processes should consider religious/cultural sensitivities, gender and minorities.

1.2.5 2.2.5 Selection of the most Appropriate Sanitation Technology

There are a wide range of sanitation technologies available for managing domestic wastewater and excreta. In addition, designing a sanitation chain means using a series of complementary components, the organization and combination which will vary according to the physical context, user demand and the level of treatment required, etc.

For a designer, selecting an appropriate sanitation solution that is adapted to the context of the local environment may be a bit complex. Wastewater and excreta management is linked to many different domains (technical, sociological, political, land use, financial, etc.) and depends on numerous criteria (topography, geology, urban population density, user demand, water consumption, temperature etc.).

Different contexts can exist each with its own particularities and requiring its own type of sanitation chain. It is necessary to consider this concept of complementary systems when defining the overall strategy at municipality level. This guide (and Steps 1 and 2 of the planning process, in particular) will enable one to identify the chain(s) best suited to the particular locality.

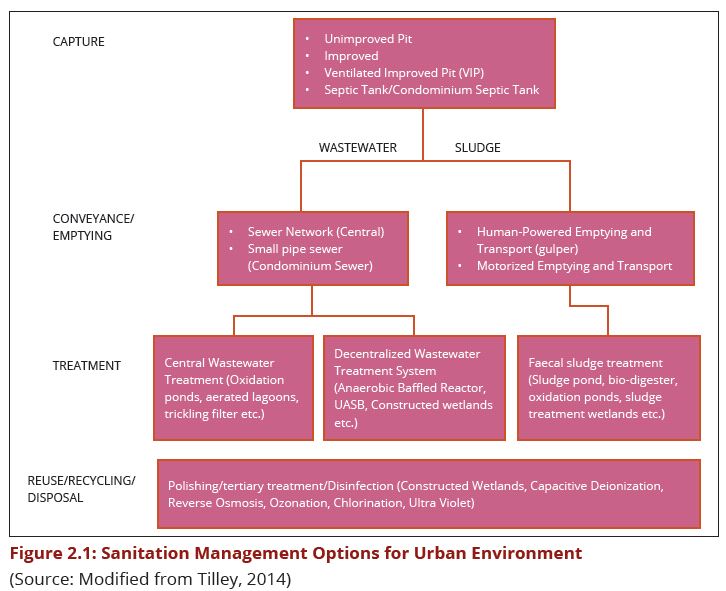

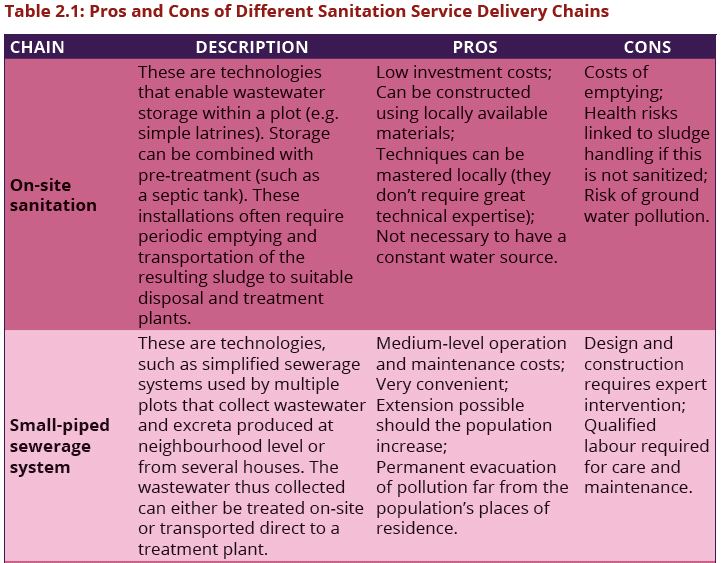

1.3 2.3 PLANNING FOR VARIOUS SANITATION CHAINS

The Urban environment in developing countries (DCs) is not uniform. Urban and peri-urban areas differ greatly particularly in terms of existing sanitation facilities. Similarly, within the urban area, different sub areas differ in terms of sanitation facilities and their connectivity to central systems. A good example is the Dar es Salaam City where there are areas which are planned and others which are not planned. Some of the areas can be connected to the central sewer but others cannot. Different types of sanitation technologies, which evolve over time, use either improved on-site systems, or small-piped or conventional sewerage systems. The relevant management option for urban environment is shown in Figure. 2.1. Sanitation system is selected by considering the demand from the population, the requirements imposed by the natural environment, the local context, the population density and local practices. Given these considerations, the different sanitation service delivery chain are defined in Table 2.1.

At local authority level, it is important to consider these different systems (onsite sanitation, small-piped and conventional sewerage systems) as being complementary to each other several sanitation chains can co-exist within the same area.

In practice, this is very common and is encouraged. The urban development of a commune (local authority) is never uniform. Different contexts can exist side by side; each with its own particularities and requiring own type of sanitation chain. It is necessary to consider this concept of complementary systems when defining the overall strategy at municipality level. This design manual (and Steps 1 and 2 of the planning process, in particular) will enable one to identify the chain(s) best suited to the particular town or part of a town or locality.

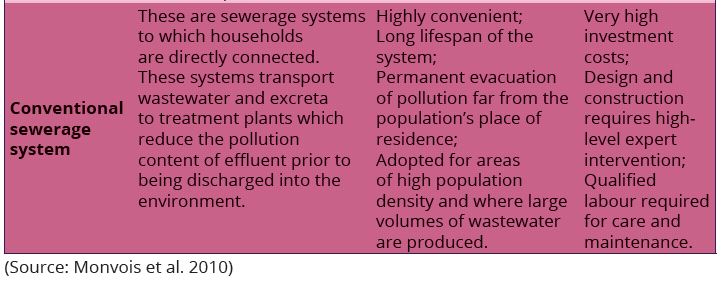

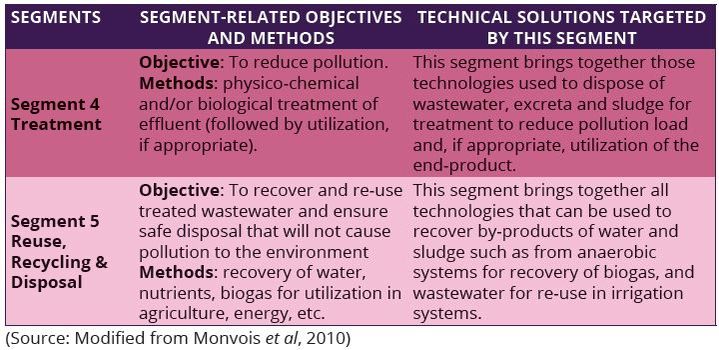

1.3.1 2.3.1 The Five Successive Segments of a Sanitation Chain

Regardless of the sanitation chain under consideration, the management of wastewater and excreta can generally be divided into five segments, as shown in Table 2.2. Breaking down sanitation into successive segments in this way enables one to better understand how complex this field is. Indeed, each segment has different, yet complementary, objectives and sets out a specific approach for meeting the requirements.

It is vital that, there is coherence between these five successive segments (and so between the different technologies used); to ensure this coherence is in place for a given area and for each of the segments, it is necessary to choose technologies from the same sanitation chain (on-site, small-piped or conventional sewerage system). Within each segment, there are specific technologies available that enable the required objectives to be met. It is these technologies that are the focus of this guide. Upon completion of Step 3 of the planning process, one will be in a position to select the appropriate technologies to be put in place.

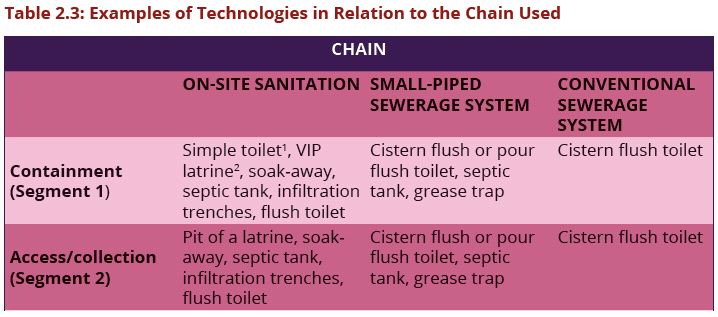

Specific technical solutions for each chain and for each segment Sanitation technologies are very diverse and vary according to both the sanitation chain used and the segment within the chain. This ‘chain’/‘segment’ double entry is summarized in a non-exhaustive manner in Table 2.3.

1.3.2 2.3.2 A Three-Step Planning Process

To determine the relevant sanitation technologies, a designer is advised to use a

three step process (Monvois, 2010), comprising: (1) Characterization of the town

with regard to sanitation situation, (2) Determination of a sanitation chain for

each area identified and (3) Selection of appropriate technical solution for each

sanitation chain.

The steps are further explained in detail below:

Step 1. Characterizing the town with regard to sanitation

A first ‘sub-step,’ (characterize the town in its entirety), provides an understanding

of the sanitation situation at overall town level enables one to anticipate any

urban development that may take place over the next 10 to 20 years. This is then

followed by a more refined analysis (characterize the neighbourhoods to identify

homogeneous areas) to identify areas that are homogeneous in terms of physical,

urban and socio-economic context. An appropriate sanitation technology that is

adapted to the context will then be implemented in each area.

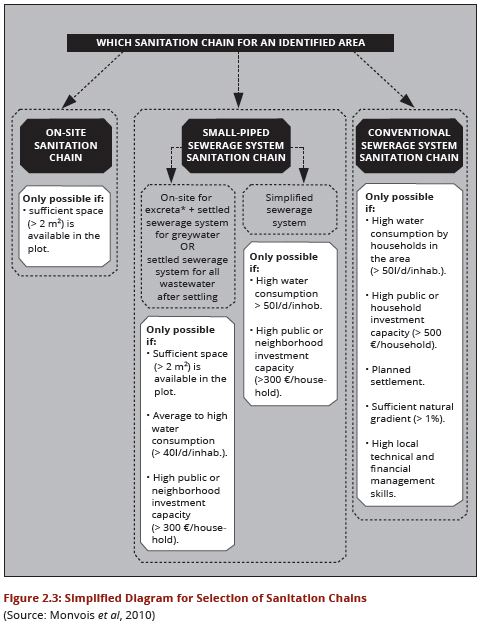

Step 2. Determining a sanitation chain for each area identified

For each of the areas identified, it is possible to select a sanitation chain based on

an initial simplified approach, as presented in Figure 2.1.This simplified approach

makes use of a limited number of the criteria for which information was collected

during Step 1 and which needs to be satisfied to validate the selection of a given

chain. One therefore proceeds by elimination. For instance, if there is low water

consumption in a given area, a conventional sewerage system sanitation chain

will not be possible. In the same way, if there is dense housing and so no space to

build a pit for a household latrine, then on-site sanitation will not be appropriate.

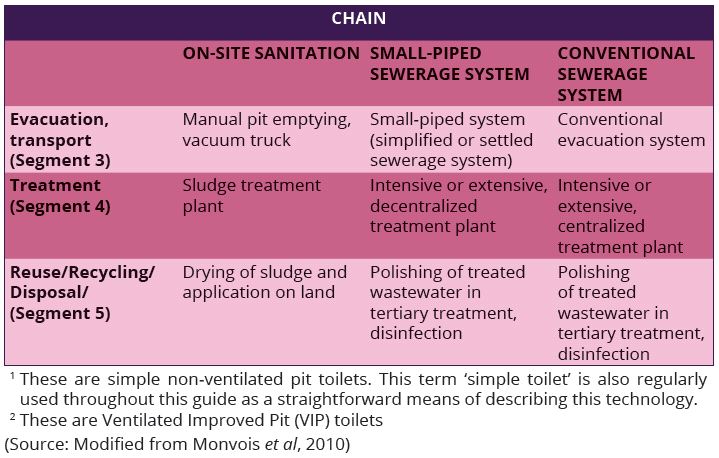

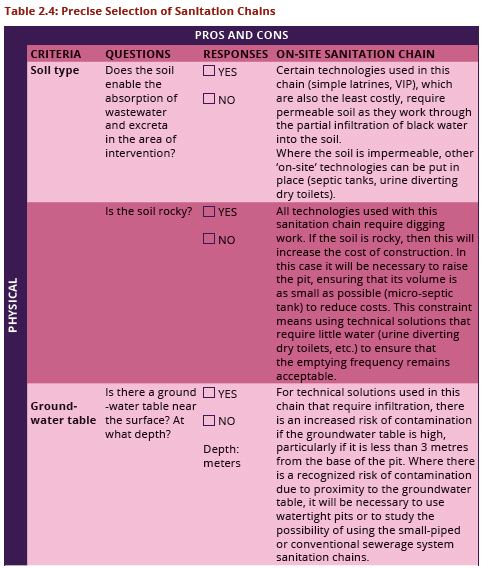

It may however, be the case that, based on the simplified approach shown in Table 2.1, several sanitation chains are possible for the same area. This type of situation is not unusual. To deal with such a situation, a second qualitative approach is proposed in Table 2.4.

This table describes the pros and cons of each sanitation chain based on indicators previously identified at Step 1.From this table, one can make a choice which, at this stage in the planning process, does not have to be definitive: if, at Step 3, it transpires that this choice is not the most appropriate. It is always possible to go back and explore a different sanitation chain for this area.

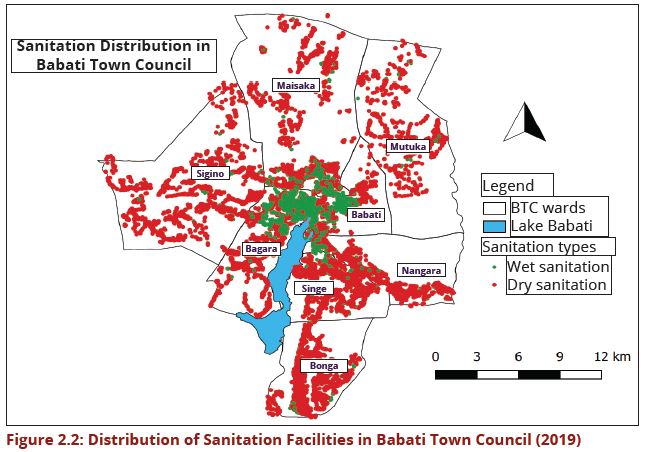

Figure 2.2 shows an example of the distribution of sanitation facilities in Babati small town. As it can be seen the wet sanitation facilities are concentrated on the Central Business District (CBD) only, while dry sanitation (various forms of pit latrines) are dominant away from the CBD. The choice of sanitation chain for the town has to take this into consideration during planning. Figure 2.3 shows a simplified diagram for the selection of a sanitation chain.

Step 3. Selecting appropriate technological solutions

The selection criteria

Each technical solution has its own characteristics, as well as its own pros and

cons. For any given area, the selection process consists of assessing the extent to

which the characteristics of a technical solution fits the context and constraints

of the area under consideration. Lastly, it is necessary to establish whether or

not a technical solution is feasible for a given area. A technological solution is

feasible if:

- it meets local demand;

- the financial resources are available for its construction; and

- the technical and management skills exist to ensure its sustained operation.

REFERENCES

Monvois, J., Gabert, J., Frenoux, C. and Guillaume, M., 2010. How to select appropriate

technical solutions for sanitation.

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (Tanzania), Office of Chief Government Statistician

(Tanzania), 2014. Basic demographic and socio-economic profile. Statistical tables.

Tanzania Mainland.

Tilley, E., 2014. Compendium of sanitation systems and technologies. Eawag.

WHO/UNICEF (2015). Joint Water Supply, Sanitation Monitoring Programme and World

Health Organization, 2015. Progress on sanitation and drinking water: 2015 update and

MDG assessment. World Health Organization.

Previous Page: Chapter One: Introduction << >> Next Page: Chapter_Three:_On-Site_Sanitation_Systems