Chapter Three: contract management

Contents

- 1 Chapter Three: contract management

- 1.1 Importance of Contract Management

- 1.2 Appointment and Roles of Project Manager

- 1.3 Contract Effectiveness

- 1.4 Contract Management Plan (CMP)

- 1.5 Contract Delivery Follow-up

- 1.6 Progress Monitoring & Control

- 1.7 Preparation of Interim and Final Payment Certificates and Managing Payments to the Contractor

- 1.8 Delays in Performance

- 1.9 Initial and Final Acceptance of the Works

- 1.10 Contract Close Out

- 1.11 Stakeholder Management Plan

- 1.12 Communication Management Plan

- 1.13 Document Control and Management of Records

- 1.14 Managing Relationships

- 1.15 Issues Management

- 1.16 Claims Management

- 1.17 Managing Contractual Disputes

- 1.18 Termination of Contract

- 1.19 Contractor’s Performance Evaluation

1 Chapter Three: contract management

1.1 Importance of Contract Management

Contract management involves activities performed by a PE after a contract has been awarded to determine how well the PE and the contractor performed to meet the requirements of the contract. It encompasses all dealings between the PE and the contractor from the time the contract is awarded until the work has been completed and accepted or the contract terminated, payment has been made, and disputes have been resolved. As such, contract management constitutes that primary part of the procurement process that assures the PE gets what it paid for. The basis of Contract management is the contract signed between the Client and the Contractor.

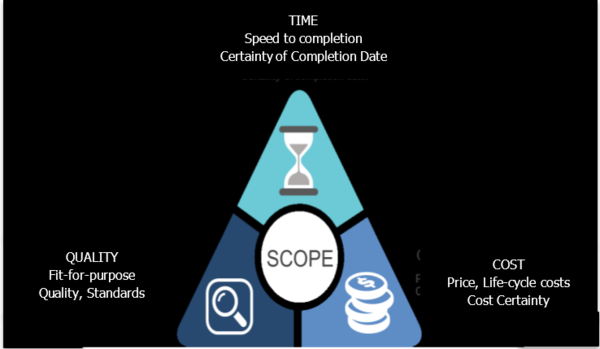

As a rule PEs are required to use PPRA Conditions of Contract drawn from Standard Tender Documents for Small Works, Standard Documents for Medium and Large Works. In situations where PPRA documents are not suitable, the contract document could be drawn from various sources such FIDIC, World Bank, European Union subject to approval of PPRA. For donor funded projects and where there is stipulation to use procurement rules of the funding agency, the documents approved by the funding agency shall be used and such approval from PPRA shall not apply. There are three aspects to a contract that must be managed while the assignment is being carried out: time, cost and quality as shown in Figure 3.1.

Time and cost must be measured against the budget and projected time required to complete the contract to detect deviations from the plan. The performance of the contract must be checked to ensure that the targets are being met.

Good contract administration assures that the end users are satisfied with the product or service being obtained under the contract. It is absolutely essential that those entrusted with the duty to ensure that the PE gets all that it has bargained for must be competent in the practices of contract management and are aware of and faithful to the contents and limits of the delegation of authority from their Employers.

Figure 3.1 Time, Cost, Quality (TCQ) Interdependencies5

There are many post-contract issues that need to be dealt with, monitored and resolved before the contract reaches its conclusion and these include the following:

- Appointment of a PM and Supervising Engineer;

- Contract Effectiveness;

- Contract Delivery Follow-up;

- Progress Monitoring and Control;

- Preparation of Interim and Final Certificates and managing payments to the Contractor;

- Delays in Performance;

- Initial and Final Acceptance of the works;

- Contract Close Out

- Stakeholder’s Management;

- Communication Management;

- Issues Management;

- Relationship Management;

- Claims Management;

- Disputes Management;

- Managing Termination of Contract;

- Evaluating of Contractors Performance.

1.2 Appointment and Roles of Project Manager

1.2.1 Appointing a Project Manager (Supervisor)

Regulation 243 of the PPR 2013 emphasizes the need for each contract, a PE to monitor the performance of a contractor entrusted to implement a contract. It is usually advisable to appoint a person within the organisation to oversee the management of a contract.

Similarly Regulation 252 of PPR 2013 provides for Appointment of Works Supervisor – normally a public officer, a unit responsible for works in PE or a Consultant- Manages the work of the inspection committee. Also Condition of Contract including those contained in PPRA’s Standard Tender Documents for Works makes it mandatory to appoint a PM. According to the documents:

The PM is the person named in the Special Conditions of Contract (SCC) (or any other competent person appointed by the Employer and notified to the Contractor, to act in replacement of the PM) who is responsible for supervising the execution of the Works and administering the Contract.

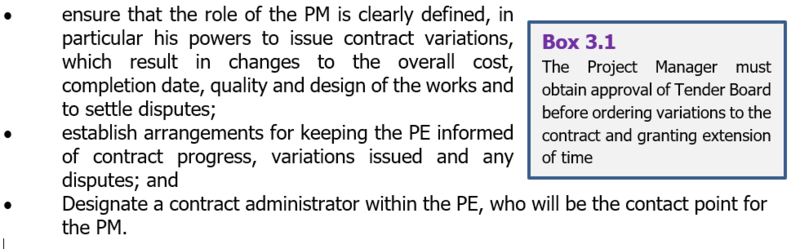

Contract management for works is often complex and time-consuming, as it involves supervision of the progress of the works, ordering variations where unforeseen conditions are encountered and measuring the works completed for payment purposes. For major contracts, a PE will normally use a full-time supervising engineer or PM, who will exercise control and supervision of the contract on its behalf. Where a PM is used, the PE must:

1.2.2 Responsibilities of the PM

As discussed above once a PM is appointed, the PE must ensure that his roles are clearly defined. The following are some of the responsibilities of the PM:

(a) Monitoring the performance of the contractor, to ensure that all delivery or performance obligations are met or appropriate action taken by the PE in the event of obligations not being met;

(b) Ensuring that the contractor submits all required documentation as specified in the tendering documents, the contract and as required by law;

(c) Ensuring that the PE meets all its payment and other obligations in time and in accordance with the contract.

(d) Ensuring that there is adequate cost, quality and time control, as required;

(e) Preparing any required contract variations or change orders and obtaining all required approvals before their issue. Such variations or change orders must be clearly justified in writing backed by supporting evidence;

(f) Managing any handover or acceptance procedures;

(g) Making recommendations for contract termination, where appropriate, obtaining all required approvals and managing the termination process;

(h) Ensuring that the contract is complete, prior to closing the contract file including all handover procedures, transfers of title if need be and that the final retention payment has been made;

(i) Ensuring that all contract administration records are complete, up to date, filed and archived as required,

(j) Ensuring that the contractor and the PE act in accordance with the Provisions of the Contract, and

(k) Discharging of performance guarantee where required.

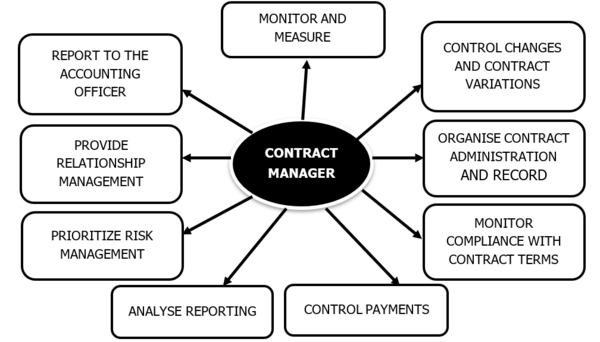

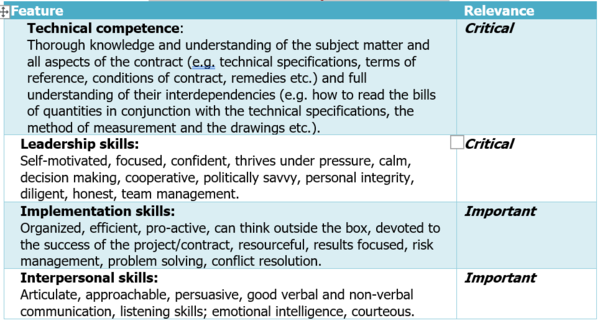

1.2.3 Requisite Skills Set of Project/Contract Manager

Good practice requires that a PM is appointed for every contract. For small, routine contracts, this may be one person, who has a portfolio of contracts to manage. For large, complex, high-value contracts this is normally an entity (Engineer, PM Etc.) The PM needs to have the appropriate range of qualifications, skills mix and experience. A project will have a good head start if it has a qualified and experienced PM. The PM, both acting on behalf of, and representing the Ministry, has the duty of ‘providing a cost-effective and independent service, selecting, correlating, integrating and managing different disciplines and expertise, to satisfy the objectives and provisions of the project brief from inception to completion. The service provided must be to the Ministry’s satisfaction, safeguarding its interests at all times. The key role of the PM is to motivate, manage, coordinate and maintain the morale of the whole project team. This leadership function is essentially about managing people and its importance cannot be overstated. A PM needs to multi-task, as for example, shown in Figure 3.2.

Hard skills - technical skills

Typical technical skills, knowledge and experience required include:

(a) Procurement;

(b) Project management;

(c) legal knowledge (at the very least an ability to understand the legal aspects of the contract, including remedies);

(d) Financial management;

(e) Analytics and reporting;

(f) Administrative, record keeping.

Additional skills may be required because of the subject matter or complexity of the contract. It is essential to have access to sufficient skills and experience as and when required. For example: civil engineering, water engineering; environmental and/or social knowledge and skills; and safety expertise;

Soft skills – interpersonal skills

In addition to technical (“hard skills”), a range of “soft skills” are required to build a successful relationship with relevant stakeholders, and to build successful contract management teams. Examples of relevant soft skills include: leadership, motivation and team building; decision making; interpersonal, communication and relationship management; mentoring and knowledge transfer; negotiation and conflict resolution; time management; and goal orientated, outcome focused.

Some of the key skills that a PM may normally possess are listed in Table 3.1.

1.3 Contract Effectiveness

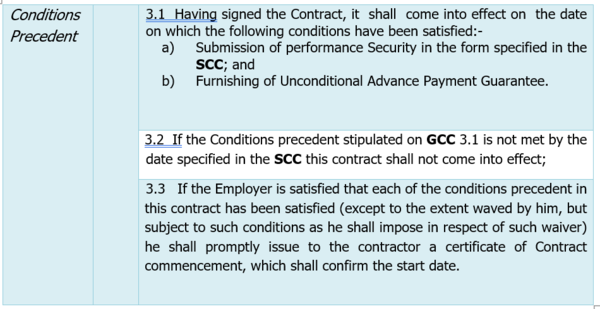

Although the contract may have been signed by both parties, the legal effectiveness of the contract may be dependent on one or more of the following conditions: (1) Receipt by the PE of the Performance Security; (2) Receipt by the PE of an Advance Payment Security; (3) Payment to the Contractor an Advance Payment; and/or (4) Mobilization and Site possession by the Contractor. PPRA’s General Conditions of Contract for works provides conditions for contract effectiveness, reproduced below, which must be observed by the PEs.

Therefore, a person responsible for Contract Management i.e. the PM needs to ensure that:

- Any Performance Security specified in the contract is received by the PE, failure of which means that there is no contract;

- Any Advance Payment specified in the contract is paid immediately when the Advance Payment Security is received from the Contractor;

- Both the Performance Security and Advance Payment Security submitted by the Contractor are verified with the issuer of the same, to avoid possibility of forgery. This should be done through official correspondences which shall be filed in the Contract File.

- Once issued with a certificate of Contract Performance, the Contractor meets the agreed dates for mobilization and possession of the site.

1.4 Contract Management Plan (CMP)

The Contract Management Plan is an input/output document that outlines the method in which a specific contract will be administered and executed. The CMP document will traditionally include a number of items such as requirements of documentation delivery and requirements of performance. A CMP can come in many forms. They can be formally written documents, in which nearly every detail is touched upon, or they can be written very informally, containing only top level information which can be filled in with more specificity at a later time. CMPs, as with most elements of the effective management of projects, should in fact be implemented as early in the life cycle of a project as possible.

In the event circumstances change, it may be possible to modify a CMP with the agreement of all parties. Make sure every contract management is tailored to the individual contract - the content and amount of detail will depend on the nature of the services, the clients and the contract. The plan should set out:

(a) who will be responsible for managing the delivery of the contract,

(b) the nature and extent of engagement with the supplier or provider,

(c) how issues and disputes will be resolved,

(d) potential risks, how they'll be mitigated and managed and by whom,

(e) a methodology and plan for evaluating the quality of delivery and the benefits achieved,

(f) key stakeholders (internal and external) and how these relationships will be managed,

(g) an exit strategy to be applied at the end of the contract.

The PM shall prepare a CMP which shall give a background of the contract and capture the key focus areas of the contract, and this may as well be a subject of discussion in the Project Kick-Off Meeting discussed in Section 3.3.2.2

It shall contain the following.

(a) Background Information.

(b) Contract management team.

(c) Contractor details.

(d) Scope of contract management.

(e) Key provisions of the contract.

(f) Duties and responsibilities.

(g) Communication channels.

(h) Review and reporting requirements.

(i) Activities and timescales.

(j) Any other information which will assist the contract management team in its task.

A Template for typical Contract Management Plan is attached as Appendix 1.

1.5 Contract Delivery Follow-up

1.5.1 Definition of Contract Delivery Follow-up

One important aspect of contract management is to follow up on the state of what has been bought after it has been delivered, to ensure that the PE is satisfied. The extent of the follow-up may vary, depending on the contract value. Responsible PE staff should establish any expected delivery follow-up requirements at the time the contract is being set up. In many cases, problems arise during implementation because mitigating measures were not taken into account during the preparation of the contract.

It is normally required to deal with reports of unsatisfactory performance immediately. Decision must be made on a contractor who is not executing works to the expected quality standards or who has delayed the works on whether it should be considered as a contract default and what steps should be taken.

Contract delivery follow-up is also responsible for dealing with a contractor whose works during the execution or during the defects liability period have become defective or fail to meet contract requirements as a result of faulty construction, materials or workmanship.

1.5.2 Contract File

In order to allow for effective contract delivery follow-up, the PM is required to open and keep a contract file after the contract is signed. The Contract File supersedes the Procurement File which is used for the purpose of keeping all important records of the procurement process until a formal contract is entered.

It is important to appreciate that proper record keeping is fundamental to contract administration. Therefore a contract file is used for recording all information regarding the actual performance of the requirements of the contract. The file should contain the following:

(a) Signed original procurement contract

(b) Any signed modifications to the contract

(c) Contract correspondence between the parties

(d) Information on performance

(e) Correspondence relating to the contract

(f) Management progress reports

(g) Minutes of meetings of project team

(h) Payment records and close up documents

(i) Copy of performance security (where required)

(j) Any other relevant information.

PPRA has prepared a guide of records to be maintained in the procurement and contract file as shown in Appendix 2.

1.5.3 Contract Delivery Follow up for Works

In works contract delivery follow-up encompasses the following:

(a) ensuring that the actual mobilisation and completion dates are agreed with the contractor, based on the date of contract

effectiveness;

(b) monitoring the overall progress of the works and the performance of the PM;

(c) reporting any contractual problems or requests for contract amendments to the PMU;

(d) checking and ensuring that invoices and supporting documentation for payment are correct and arranging payment;

(e) managing any securities, such as performance or payment securities, by ensuring that they are kept securely, ensuring that extensions to their validity are obtained in good time, when required, reducing their value when required, and releasing promptly, when all obligations have been fulfilled;

(f) ensuring all final acceptance and hand-over arrangements are completed and documented satisfactorily; and

(g) ensuring all final drawings, manuals etc. are received and kept in an appropriate place.

One of the serious problems in project implementation is the lack of a dedicated person at the Head Office who has the responsibility of following up and overseeing those decisions required at the Head Office relating to a particular project are made in time. This leads to a situation where a project’s progress is affected because of lack of timely decisions/approvals which are required to enable smooth execution on the part of the contractor. It is therefore important for a PE to appoint a dedicated person in its headquarters who shall be responsible to oversee the affairs of the project. This person is sometimes known as a Project Coordinator to distinguish him from the Project Manager.

1.6 Progress Monitoring & Control

1.6.1 Site Recording and Control Tools

1.6.1.1 Site Records

The keeping of continuous and comprehensive site records provides an effective means of controlling and monitoring all activities of a project on the site. Records have a vital role to play in the assessment and settlement of disputes. They can take a wide variety of different forms and the following list embraces most of the more common records kept by the contractor’s representative.

(a) All correspondence between a contractor and PM, including PM’s instructions, variation orders and approval forms,

(b) All correspondence between the Contractor and the Employer and third parties,

(c) The minutes or notes of formal meetings,

(d) Daily, weekly and monthly reports submitted by the Contractor’s staff,

(e) Plant and labourers’ returns,

(f) Work records such as dimension books, timesheets and delivery notes,

(g) Day work records,

(h) Interim statements as submitted including any corrections, with copies of all supporting particulars and interim certificates,

(i) Level and survey books, containing checks on setting out and completed work,

(j) Progress drawings and charts and revised drawings,

(k) Site diaries, laboratory reports and other test data,

(l) Weather records,

(m) Progress photographs and

(n) Administrative records, such as leave and sickness returns, and accident reports?

1.6.1.2 Site Correspondence

All letters, faxes, e-mails, drawings and other documents should be recorded as they are received or dispatched, and all incoming documents should be date stamped. Verbal instructions from the PM and telephone conversation where they convey instructions or important information should always be confirmed in writing. Copies of all correspondence, whether in the form of formal letters or handwritten notes, should be carefully retained, along with old diaries, notebooks, field books and similar data. The originals of every incoming letter and clear copy of every outgoing correspondence, with any enclosure, should be placed in a file containing a suitable reference title. Additional but rather time consuming and costly measures that are sometimes taken include the keeping of a register of all correspondences and making extra copies of each outgoing letter which is kept in a file.

1.6.1.3 Site Reports

A report is primarily a summary of information and the principal method of conveying information on site matters to the head office, the employer and other parties. Daily reports by Supervisors on site, form an important part of site communications. These reports contain details of the work carried out, weather conditions, the number of employees engaged on the work number and types of plant in use and hours worked, and details of any delays and their causes. Starts and completions of activities should be noted. After having been processed, the reports should be filed and stored neatly and chronologically for ease of reference. Technical reports may be prepared on laboratory tests and special reports on specific problem areas.

1.6.1.4 Labour and Plant Return

The contractor’s labour and plant returns constitute another commonly employed form of written record, the contractor will normally be required by the PM to submit at prescribed intervals, such as monthly, the number and categories of labour and plant engaged on the site. Apart from this requirement from the PM, such records assist the contractor to establish how efficiently he is utilizing his labour force, especially when such records are accompanied with the amount of work done on a daily basis for various categories of labour.

1.6.1.5 Laboratory Tests

Laboratory reports and other test results are normally entered on standard forms and files on a subject basis. Common tests include concrete cube strengths, earthworks density, compaction and moisture content, and analysis of bituminous products. On occasions, the information is more effectively presented diagrammatically as in the form of graphs for matters such as standard sieve analyses. Statistical analysis of data can encompass the determination of such parameters as range, standard deviation and coefficient of variation. The laboratory may also undertake the recording of rainfall, temperatures, wind speeds and tides.

1.6.1.6 Photographs

It is good practice to take photographs of the main features of the project from the same position at regular intervals, often monthly, to provide an excellent record of progress throughout the project. These photographs are often supplemented by photographs of particular features such as rejected section of honeycombed concrete, irregular brickwork, bank slippage and extent of flooding resulting from exceptionally heavy rainfall. The photographs should be taken with a good quality camera and they should have details of the date, subject, position and direction from which it was taken recorded.

1.6.1.7 Diaries

Diaries are indispensable as they provide a complete narrative of the progress of the works and the activities of the Contractors. The diary entries collectively supply comprehensive information on all aspects of the works and also permit cross checking to elucidate disputed statements. A diary provides a factual record of events on site, discussions with the PM’s staff and other personnel, instructions issued and weather conditions. All entries must be accompanied by details of the time, location and personnel involved.

1.6.2 Project Meetings

1.6.2.1 Purpose of Meetings

During the course of a contract, a variety of meetings will take place in site offices, on specific parts of the works and in the suppliers’ premises. Some may be called at short notice to resolve a problem on the site, while others will be formally arranged at regular intervals and are generally concerned with co-ordination and progress. The main objective of all meetings is to come to a decision, although supplementary aspects like generation of ideas and discussion of problems may also be important. Meetings can, however, fail to achieve these objectives through over-formality, ineffective chairmanship, failure to concentrate on key issues or an antagonistic attitude by one of the parties.

Information meetings are generally concerned with the removal of unacceptable work or materials or the continuance or discontinuance of a particular method of operation. A note in the participant’s diary may be sufficient to record the incident and the action taken. Where, however there is a dispute over facts or liability, then the PM may call a meeting with a Contractor’s representative by notifying him, of the proposed daytime and place of the meetings, the names of those invited and the substance of their discussion.

From time to time, it may be necessary to convene a formal meeting to discuss a specific matter which has become important to the progress of the project. Three important categories of meetings can be identified:

a) Discussion between senior members of the site organization, often involving the contractor’s representative and the PM

b) Meetings with the sub-contractor and suppliers, and

c) Meetings involving a third party, such as a statutory undertaker

1.6.2.2 Project Kick-off Meetings

Projects do not always go through an organized sequence of planning, approval and execution. Sometimes one can be executing a project and finds that team members and stakeholders have varying levels of understanding about the purpose and status of the project. Just as a project should have a formal end-of-project meeting to signify that it is complete, it also makes sense to hold a formal kickoff meeting to start a project.

Items of agenda for the Meeting

Regardless of who is in attendance at the kickoff meeting, there are a host of topics that should be covered or at the very least be touched on. These can be grouped into: project plans, ongoing concerns, and closeout.

The Project Plans

This includes the actual drawings and specs for the project. But it is also important to discuss things like the schedule, what permits need to be pulled, proposed start and finish dates for specific trades, and it is important to identify key milestones for the life of the project. Finally, when everyone leaves a kickoff meeting, they should have a concrete understanding of where their scope of work begins and ends.

Ongoing Concerns

It is a good idea to agree on meetings to be set- weekly or monthly meeting schedules during the kickoff meetings. Other topics to be covered should include: payment schedules, processes for implementation of change orders, the submittal and approvals process, and how much retainage will be withheld from progress payments. How and when material deliveries should take place might also be discussed. Not to be overlooked is safety – safety protocols and procedures should be discussed from the get-go, and it is probably a topic that should come up often at weekly meetings, too.

Closeout

It may seem a little early, but it is a good idea to discuss closeout procedures as early as possible. Information like when retainage will be released, punch list procedures, and cleanup requirements should be relayed early. That way, when the end of the job comes around, no one will be surprised when they are confronted with punch work, waiver requests and clean up.

Agenda for Kick-off Meetings

To achieve desired outcomes, it is essential to prepare a detailed agenda. Items that should be covered include:

(a) Introduction,

(b) A review of the meeting objectives,

(c) Defining responsibilities of team members,

(d) Defining communication protocols for processes of sending and approving messages,

(e) Deliverables, including ensuring client understanding of deliverables, identifying which deliverables are required prior to construction release, discussing scope of changes and related issues such as safety and quality control, bonding and insurance, and updating implementation schedules,

(f) Reviewing contract clauses,

(g) Discussing site-specific facility access and security requirements, if any,

(h) Detailing design and construction schedules,

(i) Environmental health and safety planning,

(j) Outages and permits,

(k) Planned agenda structures for plan of the day/plan of the week/ plan of the month meetings.

1.6.2.3 Project Progress Meetings

The other most important meetings on a project are the regular project meetings, sometimes termed site meetings or progress meetings. They are normally held at monthly intervals and they provide the opportunity for a regular, comprehensive re-appraisal of the project. These meetings are usually chaired by the PM. They permit a full and frank discussion of the contract, the giving of early notice of disputes which may not be capable of resolution at site Level and the receipt of any legitimate complaints against the performance of the contractor. The main functions of project meetings are as follows:

(f) To check that variations are confirmed in writing and that work is recorded and agreed.

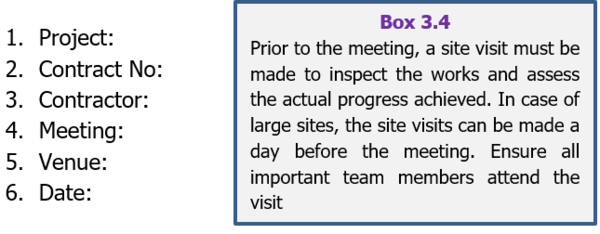

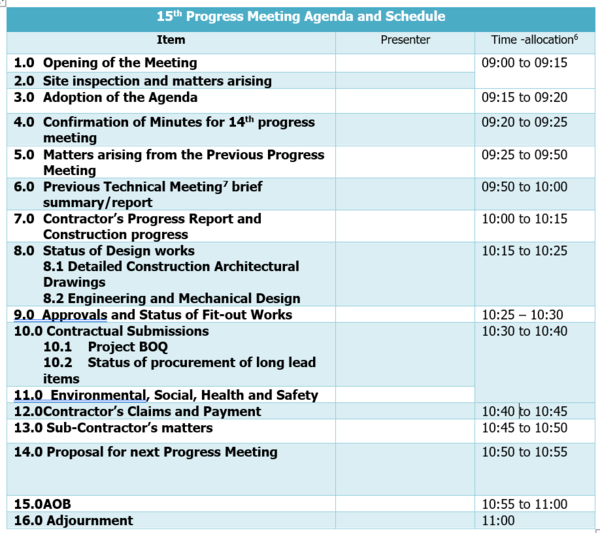

Agenda A formal agenda should be prepared for each project meeting to provide a sound basis for discussion at the meeting. Table 3.2 Shows a Typical Agenda for a Monthly Progress Meeting.

1.6.2.4 Conduct of Meetings

The chairman of the meeting, in consultation with the secretary, should ensure that dates for meetings are fixed, venues reserved and all participants are notified. The chairman will approve the agenda and usually give members the opportunity to suggest additional items for inclusion. He will also ensure that they arrive adequately prepared. A chairman should desirably be impartial, reasonable and responsive. Formal minutes or notes will be taken of the main points discussed and decision made.

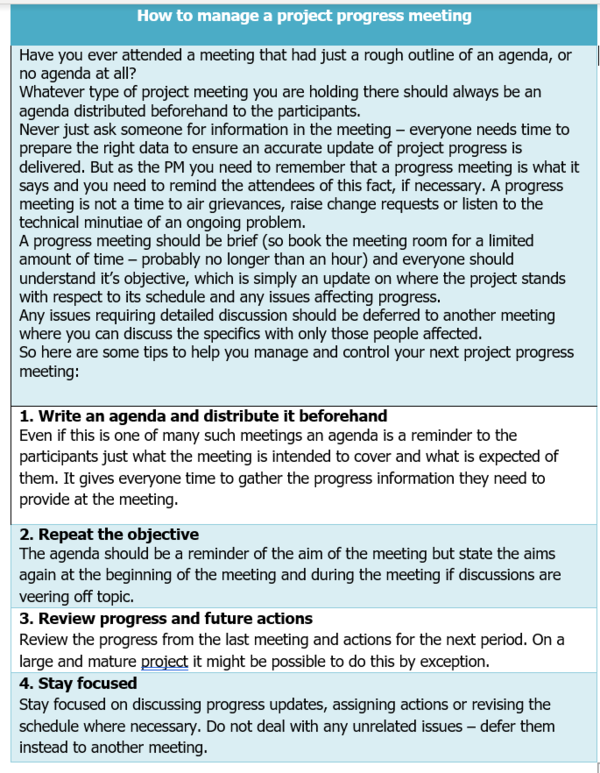

The chairman should plan the discussion around the agenda to enable members to make a positive contribution and to ensure the smooth and rapid progress of the meeting. The main objective should be to reach unanimous decision in a minimum time. An efficient chairman will at the outset of a meeting determine the purpose of the meetings its direction, the limits of discussion and the timescale. The Box 3.5 gives some tips on how to hold and manage project progress meetings. The same tips are applicable to any important meetings. Box 3.5- Tips on How to Manage Meetings

1.6.2.5 Implementation of Decisions

At the meetings views are exchanged, proposals generated and decisions made. It still remains for the decision to be implemented. The chairman of the meeting, possibly assisted by the secretary, will be responsible for ensuring implementation. The minutes will record who is to take the appropriate action and all participants will receive copies of the minutes. The action taken will be monitored at the next meeting under matters arising.

1.7 Preparation of Interim and Final Payment Certificates and Managing Payments to the Contractor

1.7.1 Advance Payment

An advance payment, sometimes referred to as a down payment, is sometimes payable when part of a contractual sum is paid in advance of the exchange, i.e. before any work has been done or goods supplied. On a construction project, a contractor may request an advance payment to help them meet significant start up or procurement costs that may have to be incurred before construction begins. For example, where they have had to purchase high-value plant, equipment or materials specifically for the project.

For the purpose of receiving the Advance Payment, the Contractor is required to make an estimate of, and include in its Tender, the expenses that will be incurred in order to commence work. These expenses will relate to the purchase of equipment, machinery, materials, and on the engagement of labour during the first month beginning with the date of the PE’s “Notice to Commence” the works as specified in the Special Condition of Contract (SCC).

In a situation where there are problems of delayed payments, it is particularly recommended that advance payment be paid to the contractors to enable smooth contract start up. However advance payment would only be paid upon submission of advance payment security in the form of Bank Guarantee . The submitted Bank Guarantee should be checked of its ‘’wording’’ to conform to the format provided in the Tender Document and its authenticity by formal communication with the issuer of the said guarantee. The Guarantee shall remain effective until the advance payment has been repaid, but the amount of the Guarantee can be progressively reduced by the amounts repaid by the contractor.

It should be noted that submission of unconditional advance payment guarantee is a condition precedent to contract effectiveness. This provision in the contract needs to be treated carefully. Sometimes a contractor may face difficulties to process and submit an advance payment guarantee- under such circumstances wisdom should prevail. The PM may suggest amendment of the contract subject to the approval of the TB to disable payment of advance payment clause in the Contract so as to allow the contract to be effective without there being a need for the contractor to submit an advance payment guarantee . Once the advance payment clause is disabled, obviously the contractor will not be paid advance payment.

Also important to note is that delay in payment of advance payment is a compensation event which may entitle the contractor to an extension of time. Therefore immediately after the contractor has furnished acceptable advance payment guarantee, payments of the same should be effected within the date specified in the SCC.

It is also important to note that the Contractor is required to use the advance payment only to pay for equipment, plant, materials, and mobilization expenses required specifically for execution of the Contract. It is therefore the duty of the PM to obtain evidence from the Contractor that advance payment has been used in this way by supplying to him copies of invoices or other documents as may be appropriate.

1.7.2 Interim Payment Certificates

Interim Payment Certificates (IPC) provide a mechanism for the client to make payments to the contractor before the works are completed. Interim payments can be agreed in advance and paid at particular milestones, but they are more commonly, regular payments, the value of which is based on the value of work that has been completed (this is the actual value of the work completed, taking into account variations, etc.). The amount of these payments is entered onto an interim certificate and the client must honour the certificate within the period stipulated in the contract.

The value of an interim certificates is the value of the work completed, less any amounts already paid, less retention. Half of this retention will be released on certification of practical completion and the other half upon issue of the certificate of making good defects. Normally the value of work executed is required to comprise the value of completed work items in the Bill of Quantities (BOQ). In addition, it should include valuation of Variations and Compensation Events. The PM may exclude any item certified in a previous certificate or reduce the proportion of any item previously certified in any certificate in the light of later information.

Interim certificates should make clear the amount of retention and a statement should also be prepared showing retention for nominated sub-contractors if there are any. There may be particular provision to include the value of particularly costly materials that the contractor has delivered to the site. This allows the contractor to order items in good time, without incurring unnecessary long-term expense, but does put the client at some risk if the contractor becomes insolvent.

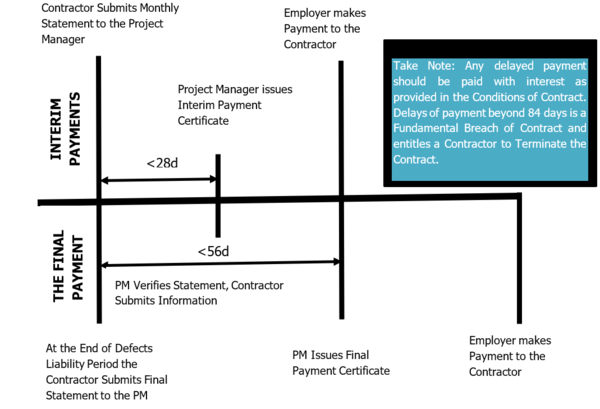

PPRA’s Conditions of Contract provide that the PM must issue an interim certificate within 28 days after the contractor has issued an interim payment application. The PM will also need to ensure that the amount of IPC exceeds the minimum amount of IPC provided in the SCC. Figure 3.3 shows a typical sequence of payments as envisaged in a typical construction contract.

1.7.3 Final Payment Certificate

The Final Payment Certificate (FPC) is certification by the PM that a construction contract has been fully completed. It is issued at the end of the defects liability period and has the effect of releasing all remaining money due to the contractor, including any remaining retention. The value of the final certificate will be based on the final account agreed by the PE and the contractor. This means that all patent defects must have been remedied, all adjustments to the contract sum must have been agreed and all claims settled.

Where proceedings have been commenced in relation to a dispute, the conclusiveness of the final certificate is a subject of the findings of those proceedings. In addition, the final certificate itself can be disputed. Adjudication, arbitration or other proceedings may then be necessary to resolve the dispute. The final certificate is then only conclusive in relation to matters that are not disputed.

1.7.4 Managing Payments to the Contractor

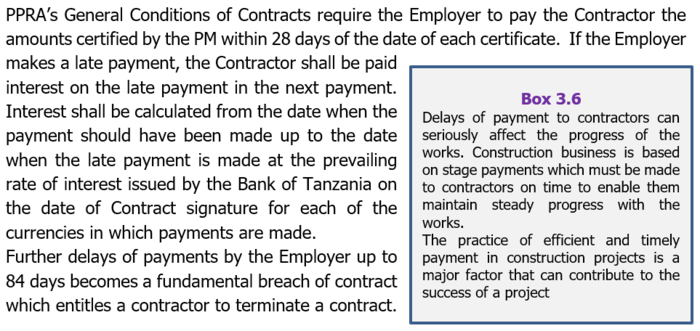

Delay in paying construction contractors has impacted negatively on the effectiveness of contractors and as such affect the project delivery schedule. Failure to pay contractors in time for work executed might lead to the contracting firm being insolvent. Delayed payments of work done on construction projects in the construction industry are considered to be a factor of significant concern. It causes severe cash-flow problems to contractors and this can have a devastating effect down the contractual payment chain. It is not uncommon to find a contractor or sub-contractor who has not been paid what is due to him threatening to suspend work under the contract until the balance due to him is paid in full. The Ministry of Water (MoW) will ensure computerization of a payment tracking system supported by a transparent queued system accessible online to all the key stakeholders

It is however unfortunate that, some PEs disable the requirement to pay interest on delayed payments through the SCC. This is not allowed as it is among the fundamental rights of the contractor to be paid on time and any delayed payment attracts interest. Contractors on the other hand are afraid to claim interests for fear of being unofficially blacklisted by the PEs. It should be emphasized here that one of the most fundamental obligation of the Client is to ensure timely payment for all works completed to the required quality. Failure to meet this obligation forces the other party to fail to meet its contractual obligations which depends on staged payments as provided in the contract.

The key considerations for effective management of payments to the Contractors:

(a) Ensure that a proper estimate is prepared for the project, and based on the prepared estimate a budget is set aside for implementing the project;

(b) Ensure that advance payment is made in a timely manner after the contractor has presented an acceptable and verified advance payment guarantee. As mentioned before, delaying payment of the advance is a compensation event which entitles a contractor to an extension of time, but more importantly it hurts the smooth start of the project and can have far reaching consequences as to the ability of the contractor to produce quality work in a timely manner.

(c) Ensure that certification for work done is done properly and in a timely manner and that payments due to the contractor are made as per Conditions of Contract. In a situation of delayed payments, it is a contractual right to pay the contractor interest for delayed payments as provided in the contract.

(d) Ensure that retention money as provided in the contract is deducted from payments due to the contractor up to the maximum amount provided in the contract. Also ensure that half of the retention money is paid to the contractor after issuance of Certificate of Practical Completion of the works.

(e) Since the management of half of the retention money which is required to be paid at the expiry of defects liability period can be a challenge to the Ministry, consider the option of paying the contractors this amount after issuance a Certificate of Practical Completion of Works subject to submission of acceptable unconditional retention money bank guarantee.

(f) Ensure that any variations to the Contract which result into an increase to the contract sum and/or construction period are approved by the TB before payment

(g) Ensure that any claims submitted by the contractor are determined fairly and in a timely manner. No variation to a contract price or construction period should be communicated to the contractor until approval of the TB is obtained.

1.8 Delays in Performance

Performance of works should be completed by the Contractor in accordance with the time schedule prescribed in the Schedule of Requirements. Where this is not the case:

(a) The PM should demand from the Contractor, in writing, the conditions delaying performance, including full details of the delay, the likely duration and the cause(s).

(b) The PM will immediately assess the situation in consultation with the PE, and may at his discretion extend the Contractor’s time for performance, with or without liquidated damages as specified in the Contract.

(c) If the time for performance is extended, both parties shall ratify such extension by a formal addendum to the Contract subject to approval by the TB.

(d) A delay by the Contractor in the performance of his obligations may render him liable to liquidated damages if specified in the contract document, except where:

- the delay is as a result of Force Majeure;

- there is no provision for liquidated damages in the contract;

- an extension of time is agreed between the two parties without the application of liquidated damages.

PMs are required to refer to the relevant clauses in the Conditions of Contract for the procedure to be followed to calculate and claim liquidated damages. They are also required to update the contract file to reflect any delays in the Contractor’s performance, and ensure that the user department (UD) is notified immediately of all such delays if they are not already aware.

Waivers to liquidated damages need to be handled carefully as they are likely to attract audit queries. Any waiver should be accompanied by an extension of time which is only justifiable when there is a compensation event as described in the contract which entitles the contractor to an extension of time.

1.9 Initial and Final Acceptance of the Works

1.9.1 Initial Acceptance of Works

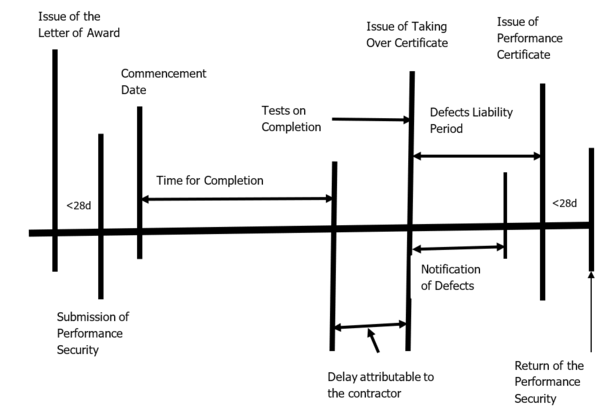

Initial acceptance of the works also known as Provisional Acceptance is a conditional acceptance which means that the client has accepted the project but performance needs to be verified or confirmed under operational conditions within an agreed period. The client issues a Provisional Acceptance Certificate to evidence this step. This is when the defects liability period starts. Initial acceptance follows practical completion of the works by the contractor.

Practical Completion doesn’t mean the Contractor has finished the Works in every detail. It means the Works are sufficiently complete to be safely used by the PE for the purpose he intended. The Contractor may still complete minor items and fix defects after Practical Completion, as long as the Employer isn’t inconvenienced. Practical Completion is important because if it is not achieved by the due completion date, the Ministry can impose penalties on the Contractor.

The PM must issue a Certificate of Practical Completion to the Contractor when he has achieved Practical Completion. Once the Certificate has been issued, the Ministry may occupy and use the Works, provided he gives reasonable access to the Contractor to finish the minor items still outstanding and to fix any defects. Although the Ministry may occupy and use the Works, the Contractor still has possession of the Works. This means the Contractor is still responsible for loss or damage to the Works, unless the loss or damage is caused by the Employer. Figure 3.4 summarizes typical sequences of events from award until completion of the contract.

Figure 3.4 Typical Sequences of Events from Award until Completion of the Contract

1.9.2 Final Acceptance

Upon completion of a construction project, the owner will “accept” the works and thereafter release final payment to the contractor. Typically, a contract sets procedures for the administrative closeout of the project, including clauses covering substantial completion, reduction and release of retention, final inspection of the works, final acceptance, and final payment.

As can be expected, contractors usually focus most heavily on what is necessary to receive final payment. However, “final acceptance” by the owner is the most important closeout event as far as the contractual and legal relationship of the parties. Under the common law of contracts, upon final acceptance, the owner takes control and ownership of the project and the risk of loss passes from the contractor to the owner. Final acceptance generally means acceptance of the works as completed, including any deficiencies known to exist. At that point, the owner’s contract rights against the contractor becomes far more limited. Therefore, final acceptance of the works should be considered the most significant contract event after contract award.

1.10 Contract Close Out

1.10.1 Contract Closeout Defined

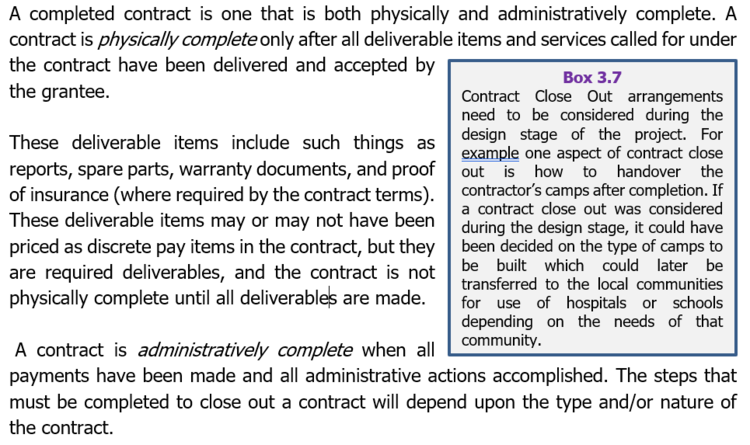

Contract close out is a part of contract management and therefore has the same purpose: to “ensure that contractors perform in accordance with the terms, conditions, and specifications of their contracts or purchase orders.” The extent of the effort involved in contract close out varies widely with contract type and the type of product or service procured. Therefore, there is no single procedure that can be used for the full range of contract types and products procured. Essentially it is a review and documentation of the fulfillment of all contract requirements.

Contract close out is quite simple with respect to a firm-fixed-price, off-the-shelf supply contract where the file contains documentation that the end product has been received, inspected and accepted and that full payment has been made. The process is more complex when large contracts containing progress payments, partial deliveries and many change orders are involved. However, the end objective is the same; to determine if the contractor fulfilled all requirements of the contract and if the PE has fulfilled its obligations.

1.10.2 Contract Completion Checklist

1.11 Stakeholder Management Plan

1.11.1 The Need for Stakeholders’ Management Plan

Managing stakeholders is an important task that must be performed by a PM in order to achieve the project outcomes. Some of the challenges found in project implementation is the stakeholder’s indifference. A stakeholder indifference can kill projects, and the lack of stakeholder participation is a common challenge in construction project management. When stakeholders are indifferent to the activity at a site, it can result in work and delays.

This process is also involved in developing management strategies to engage them throughout the life cycle of the project. PMs need to make a stakeholder management plan based on the stakeholders’ interests, needs and impact on the success of the project. The benefit of this project management process is that it provides a concise plan to interact with the stakeholders to support the project’s interest.

It also identifies how stakeholders will be affected by the project. This will allow PMs to strategize and develop ways on how to engage them effectively in order to manage their expectations in the event that will lead to the achievement of the objectives of the project. This often involves the improvement of communication channels to create a harmonious relationship between the stakeholders and the project team while, at the same time, satisfying the needs and requirements of everyone within the project boundaries.

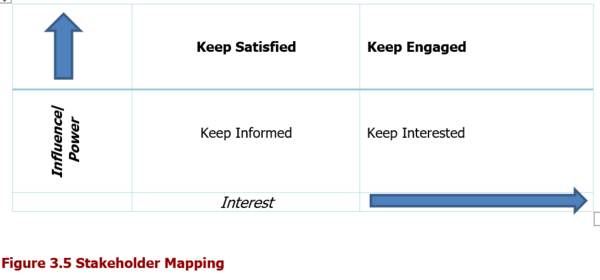

1.11.2 Stakeholder Mapping

Stakeholder Mapping is a process of finding out the key stakeholders relating to a project. The process involves identifying all individuals who have an interest in the project outcome. A project stakeholder can be one individual or multiple individuals as in the case of a large public infrastructure project.

Once all the project stakeholders are identified, the PM must map, or categorize them, according to the different levels of engagement. Mapping of the stakeholders is done according to the following two levels – the level of interest and the level of influence By influence, it means stakeholders have power in setting and modifying project requirements. On the other hand, interest means that stakeholders are affected by the project outcome but they do not have any power to influence project requirements.

A PM should focus on satisfying expectations of the stakeholders who have a high level of influence relating to the project. On the other hand, stakeholders having a high level of interest need to be merely kept informed of the project status.

Mapping of shareholders is a visual exercise. One can manually map the stakeholders. Once a PM has fully mapped the stakeholders. One may need to create an action plan on how to engage with them. The 4 steps of stakeholder mapping

- Identify top-level stakeholders, e.g. Project Team Members, staff, civil servants, politicians, associated organisations,

- Segment the top-level to make the information more meaningful, e.g. levels of membership, engaged/non-engaged members, permanent / contract staff, senior / junior roles, MPs / local councilors, specific constituencies/ wards, other membership organizations, charities, NGOs, community groups, specific interest groups,

- Establish their levels of interest and influence,

- Engage – prioritize the stakeholders to determine their level of engagement- Stakeholder Map template

To determine how one should best engage each stakeholder group, it is recommended to apply the thinking below to the groups in each quadrant:

(a) High Influence / Low Interest – communicate and engage enough so they are satisfied their voices are being heard on key issues. Avoid low value contact so they do not lose interest in what the organization is doing (KEEP SATISFIED- include in meetings/presentations)

(b) High Influence / High Interest – these need to be fully engaged and lots of effort made to satisfy their concerns and requirements for information. These will be valuable advocates. (KEEP ENGAGED – provide personal briefings/ workshops)

(c) Low Influence / Low Interest – monitor these stakeholders closely and keep them informed, with minimal effort. Do not overload them with excessive communications or needless information (KEEP INFORMED – no specific communication , incidental via third parties)

(d) Low Influence / High Interest – keep these stakeholders regularly informed to maintain their interest. Monitor any issues or concerns that may arise and respond (KEEP INTERESTED – newsletters, posters flyers, etc.)

1.12 Communication Management Plan

1.12.1 The Need for Communication Management Plan

A project communication plan is a simple tool that enables the PM to communicate effectively on a project with the client, team, and other stakeholders. It sets clear guidelines on how information should be shared, as well as who’s responsible for and needs to be looped in on each project communication.

A communication plan plays an important role in every project by:

(a) Creating written documentation everyone can turn to.

(b) Setting clear expectations relating to how and when updates will be shared.

(c) Increasing visibility of the project and its status.

(d) Providing opportunities for feedback to be shared.

(e) Boosting the productivity of team meetings.

(f) Ensuring that the project continues to align with goals.

1.12.2 Project Team Communication Methods

There is no single right way to communicate on a project. In fact, a communication plan can and should include a variety of communication methods. Here are a few to consider: Email, Meetings (in-person, phone, or video chat), Discussion boards, Status, reports, to-do lists and Surveys.

So how do you know what is right for the project? The PM should review past projects to see what worked well—and what didn’t. He/she should talk to the team, client, and other stakeholders to ensure that everyone takes their communication styles into account. After all, a weekly email is no good if no one reads it!

1.12.3 How to write a Project Management Communication Plan

Writing a project management communication plan follows these 5 steps:

(a) List the project’s communication needs. Every project is different. Take the size of the project, the nature of work being done, and even the client’s unique preferences into account as one determines which types of communication this project needs in order to succeed.

(b) Define the purpose. Bombarding people with too many e-mails or unnecessary meetings can interfere with their ability to get work done and cause them to overlook important updates. Be purposeful in the implementation of the plan, and ensure every communication included has a reason. If one is feeling really ambitious, he should go ahead and outline a basic agenda for the topics that will be covered in each meeting or report.

(c) Choose a communication method. Does one really need a meeting to share weekly updates, or is your project discussion board enough? Think through how the team works best, so they can stay in the loop while still being productive. If the client prefers the personal touch of a phone call, build that into the plan too.

(d) Set a cadence for communication. Establishing a regular frequency of communication streamlines the process by setting clear expectations from the time go. This not only frees one from fielding random requests for status updates. It also enables project members to carve out space for important meetings and reports ahead of time.

(e) Identify the owner and stakeholders. Assigning ownership creates accountability so a carefully crafted plan can reach its full potential. The PM will be responsible for most communications, but there may be some who want to delegate the communication function to others. While one is naming names, it is necessary to list the audience or stakeholders for each communication type too. That way key players come to meetings prepared to provide updates when needed.

1.12.4 Project communication plan: Examples and template

Know your team and stakeholders well. So how do you organize the details is up to you. Just be sure it is easy to understand. Table 3.2 shows an example of an effective communication management plan.

1.13 Document Control and Management of Records

All documents used throughout the project phases need to be controlled to ensure the availability of approved documents when and where needed, that obsolete documents are withdrawn to prevent inadvertent use, and that documents are identified, tracked and stored to permit efficient retrieval.

Document control procedures should achieve the following objectives:

(a) All documents are reviewed and approved by the designated personnel prior to issue for use and shall be accompanied with an approval letter signed by responsible personnel;

(b) Document changes are approved by designated personnel; where possible, the reason for changes to documents that have previously been issued shall be indicated in the document or attachments;

(c) Documents are available at locations where the use of the document is vital;

(d) The distribution of project documents is recorded and, in designated cases, controlled.

(e) A master list of all documents, indicating current authorized versions, is maintained;

(f) A historical record of project documents is maintained to record implemented changes, the proper release by authorized personnel, and distribution to the location where the prescribed activity is performed;

(g) To ensure that current information is available as required throughout the project and that obsolete information is withdrawn from use. Obsolete documents kept for historical record are identified as obsolete; and

(h) Quality records are maintained and retained in accordance with project procedures.

This electronic approach reduces the frequency with which project staff needs to remove hard copies from the project files, which in turn increases the level of control and security on the documents. However, if the hard-copy/original version of the document is needed for some reason, the user can easily determine where it is located in the project files through the coordination with the user and archives department.

1.14 Managing Relationships

1.14.1 Importance of Managing Relationships

- Reactive Approach – Where the organization starts managing the contractor relationships only when unpleasant situations with contractor occur, try to figure out how to improve the performance of unreliable contractors. This approach consumes quite a lot of time and resources, which could have been better spent on more important business processes.

- Strategic approach – This applies where a contractor relationship management starts even before an agreement with the contractor is signed, in order to ensure the competitive advantage of the company in the long run. This is a forward-focused approach, which can lead to a successful relationship even in the early stages.

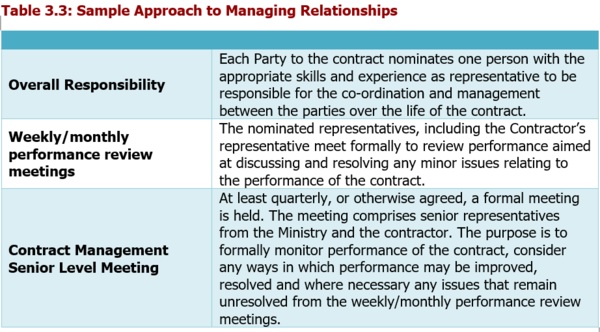

The strategic approach to contractor relationship management has always been key to successful businesses that rely on third-party contractors, regardless of industry. Table 3.3 Shows a sample of an approach of managing relationships in a construction project. The procedure to manage relationships may need to be discussed and agreed during the project kick-off meeting discussed in Section 3.6.2.2 of this manual. By agreeing beforehand on how to manage relationships, one is creating a strategic approach to handling problems on site and prevents being reactive to things when they do not go well on site.

1.14.2 Partnering as a Way of Managing Relationships

Partnering is a project approach designed to enable a construction process to run within an environment of mutual trust, commitment to shared goals, and open communication among the client, architect/engineer, construction manager, general contractor (if applicable), and subcontractors. Partnering establishes a working relationship among all of the team members based on a mutually agreeable plan of co-operation and teamwork. Parties to the design and construction process, in agreeing to work under a partnering approach, work to create an atmosphere in which all parties are working in harmony toward mutual goals to avoid claims and litigation. The partnering approach is comprehensively covered in Appendix 3.

1.15 Issues Management

1.15.1 Definition of an Issue

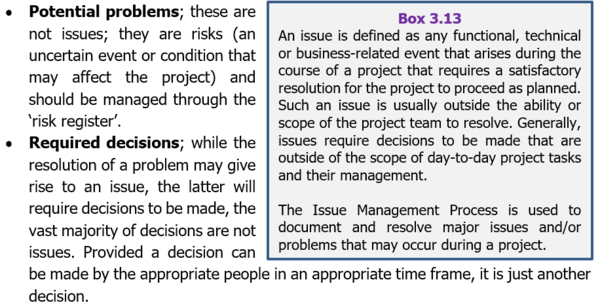

An issue is a current problem that was previously a risk to a project (whether identified or not), that will negatively impact the successful delivery of the project. In other words, each issue is a significant problem arising from a realized risk. Issues should not be confused with:

- Action items; while in many respects action items are similar to issues, they should not be confused. Action items simply require someone to take the appropriate action.

Issues are identified problems that will have a detrimental impact on the project if left unresolved and, by definition, the solution is not known until the issue is resolved. Some issues will have an immediate impact on the project; others will be a future event that will impact the project if not resolved. However, not all ‘problems’ are issues. An issue is a formally defined problem that will impede the progress of the project and cannot be resolved within the routine project management process. Generally, issues either require some ‘special effort’ by the project team, outside help, or both to resolve. To facilitate this management effort, issues are recorded in the issues log.

Fortunately, not every issue requires immediate action. Certainly, by the time it is identified many issues will have a fully developed impact that has to be dealt with quickly. Other issues will be emerging, their impact yet to be felt by the project, meaning there is time to address the problem. This allows some level of prioritization.

The analysis and prioritization of issues allows for effective management:

- Issues should have the same consequence (or impact) rating as the risk from which it was realized. This allows prioritization of action based on severity and cross links to the risk register.

- The time window for action is also important. Issues with less significant impact ratings that are impacting the project may need prioritizing over issues with more significant impact ratings that will not impact the project for some time.

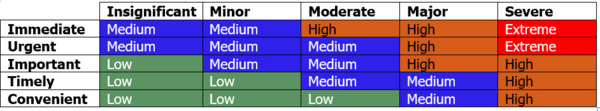

The use of an issue matrix, similar to the traditional risk matrix, allows an overall issue rating that takes into account the timing of the realized impacts. The matrix retains the consequence or impact ratings from the risk assessment. However, instead of probability, the rows now relate to ranges of time in which an issue needs to be resolved before the impact negatively affects the success of the project.

As a default position, the following definitions may be appropriate for the different time ranges:

- Immediate: Resolution needed within the next five (5) working days or project success will be impacted

- Urgent: Resolution needed within the next ten (10) working days or project success will be impacted

- Important: Resolution needed within the next month or project success will be impacted

- Timely: Resolution needed within the next month or the uncertainty over resolution will disrupt other activities or decisions

- Convenient: Decision not needed for more than one month.

Figure 3.7 The Use of an Issue Matrix The above matrix and definitions ensure that minor and moderate impact issues requiring immediate resolution will receive the same issue rating, and hence the same level of attention, as major or severe impact issues that do not need to be resolved for a month or more. If an issue is left unresolved it would automatically advance up the rows, from convenient to immediate, as the date on which resolution is required approaches, ensuring that issues that were initially assessed as having a low ranking due to their lack of proximity to the current date are not forgotten.

1.15.2 Managing an Issue

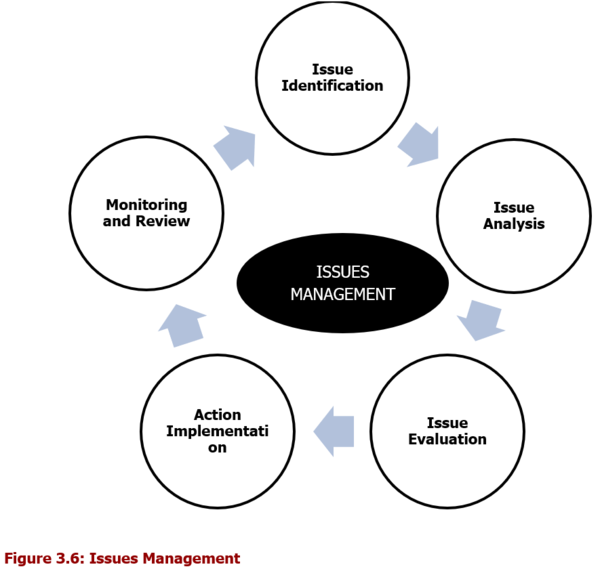

The processes used to manage issues can be simpler or more rigorous depending on the size of the project. The following process is appropriate for large projects.

(a) Identify the issue and document it: Actively seek potential issues from any project stakeholders, including the project team, clients, sponsors, etc. The issue can be communicated through verbal or written means, but it must be documented.

(b) Determine if the ‘problem’ is really an issue. Many items may be risks (potential problems that should be managed as a risk) or just action items that must be ‘actioned’ and followed-up. Issues involve a degree of uncertainty either in relation to the action (or non-action) of a stakeholder or in determining the best solution to the problem. The PM should determine whether a problem can be resolved immediately or whether it should be classified as an issue. If a large issue looks too difficult to be resolved in a timely manner, break it down into logical sub-issues.

(c) Avoid conflict! The issue is a problem to resolve; adding additional layers of complexity by introducing conflict, blame or other emotions will not help the resolution of the issue. If a level of conflict is already occurring between some of the involved parties, work quickly to resolve the conflict and focus everyone on solving the problem.

(d) Enter the issue into the Issues Log. If the problem is an issue, the PM should enter the issue into the Issues Log.

(e) Allocate an owner – the issue manager. You can't manage everything, so it is important to be able to delegate tasks. Choose someone who has the skills to help resolve the problem and ask them to be the issue manager. This means that they will have to follow up progress on resolving the issue, track the actions and provide you with status updates.

(f) Determine the impact. Using the same scale defined for the risk register (if the issue was an identified risk, transfer the relevant information from the risk register), carry out an impact analysis to assess the scale of the problem. Think about the areas of the project and the stakeholders that are affected and how long the problem will take to resolve. It is a good practice to encourage people to help identify solutions along with the issues. When a team member identifies a potential issue, ask the person to also suggest one or more possible solutions.

Determine the solution date. A ‘resolve by date’ should be defined and recorded for every issue.

(g) Priorities the issue. Use the matrix above.

(h) Determine who needs to be involved in resolving the issue. The issue manager determines who needs to be involved in resolving the issue. It is important to understand up-front who needs to be involved in, or can contribute to developing the final issue resolution. Provide guidelines for when team members can make decisions and when more senior people need to be involved. Team members should be encouraged to make the decision themselves if:

(i) Apply problem solving techniques to develop a solution. The PM should assign the issue to a project team member for investigation (the PM could assign it to himself or herself but in most cases, delegation is essential). The team member will investigate options that are available to resolve the issue, and for each option, the team member should also estimate the impact to the project in terms of budget, schedule, scope, risk and other pertinent factors such as identifying any environmental impacts.

(i) There is no significant impact to effort, duration or cost,

(ii) The decision will not cause the project to go out of scope or deviate from previously agreed upon specifications,

(iii) The decision is not politically sensitive,

(iv) The decision will not cause one to miss a previously agreed upon commitment,

(v) The decision will not open the project to future risk.

(j) Gain agreement on resolution. The various alternatives and impact on schedule and budget are documented on the Issues Form or Issues Register. The PM should then take the issue, alternatives and project impact to the appropriate stakeholders for discussion and resolution. The PM should make a recommendation and may have the authority to select from the alternatives. Each resolution should involve a set of agreed actions, and if the agreed solution involves changes to the project, the agreed solution is formalized through the change control process.

(k) Add the action plan to the project management plan. Once a resolution is agreed upon, the appropriate corrective activities are added to the schedule and other documents to ensure the agreed resolution to the issue is actually implemented (particularly if the change control processes are not required).

(l) Monitor progress. Use the action plan and project schedule to monitor progress towards resolving the issue. Follow up with the issue owner on a regular basis. When each action has been completed successfully, you can mark the task as complete on the task list and update the issue log with the latest progress.

(m) Review and Close the Issue in the Log. The PM should document the resolution or course of action in the Issues Log, reviews the overall effectiveness of the solution and where appropriate records the lessons learned.

(n) Communicate through the Status Report. The PM should communicate issue status and resolutions to project team members and other appropriate stakeholders through the methods established in the Communication Management Plan, including the project Status Report. Smaller projects may not need all of these discreet steps. For instance, the issue can be documented and rated directly in the Issues Log without the need for the separate Issues Form but all well managed projects should develop a process that manages issues from identification through to completion and closure.

1.15.3 Issues Log

The format and contents of an issues register needs to be adapted to the project and should be based on an organizational standard (organizational process asset). Most issues logs contain the following information:

(a) The issue name (unique and short).

(b) Classification or type (usually based on what aspect of the project’s work is affected; safety/quality/etc.).

(c) Status:

(i) Pending (the issue is not fully defined yet).

(ii) Open (it is being worked on).

(iii) Closed (it has been resolved).

(d) Who raised the issue (normally this person needs to know when and how it is resolved).

(e) Date the issue was raised or logged.

(f) A concise description of the issue and references to other relevant documents.

(g) Priority (see matrix above). The issue owner or manager (the person tasked with resolving the issue).

(h) Resources assigned to work on the issue.

(i) Target resolution date.

(j) Final solution (this should be distributed and actioned).

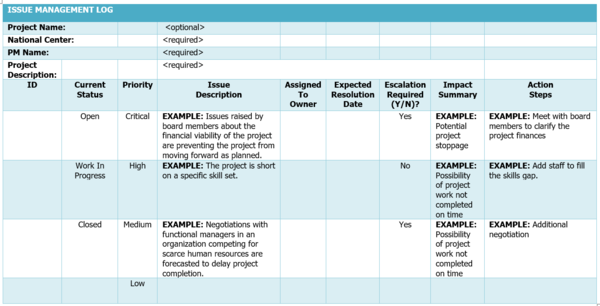

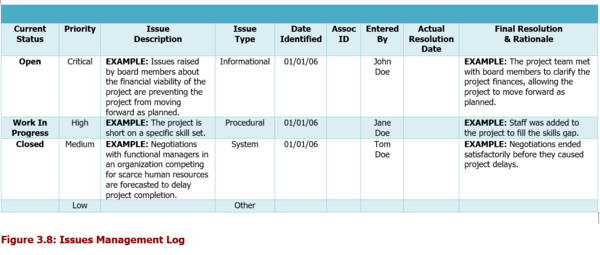

The log can be set up in a database, spreadsheet or ‘Word’ document. An Example of Issues Management Log is attached as Figure 3.7.

1.16 Claims Management

1.16.1 Definition and Objective of Claims

A claim arises when one party, mainly to a contract, believes he has suffered a detriment for which the other party should compensate him. A claim can be defined as a demand, or request, for cost or time compensation, over and above that which has been granted or contemplated, from one contractual party to the other. The objective of all claims is to put a party back in the position he would have been in but for the delay or disruption; the original profit (or loss) should remain as included in the tender.

It is a misconception to believe that claims are a substitute for a well-prepared tender and will compensate a contract for the deficiencies on his tender. Neither will a claims approach put a contractor back into a position of positive cash flow where he has deliberately pitched his price at a sub-economic level in order to keep his resources occupied. All too frequently contractors, see claims as being methods of compensation for situations where it is the contractor who has placed himself in a position of uneconomic contracting. A claim is most definitely not the difference between what one thought the job would cost and what it actually cost. Many experienced contractors still seem to believe in this definition.

Neither should employers expect to finish the contract for the price of the contractor’s tender, more particularly where the conditions of contract provide a mechanism for variations to be instructed by the PM and for extensions of time to be granted for a variety of different circumstances.

If employers want the lump sum price without the possibility of changes affecting the contract price, then far more care needs to be taken in the period leading up to the tender, and the extent to which the design is compete will have a fundamental bearing on the ultimate price outcome.

It is not unusual for an employer’s professional team to spend months preparing the documentation for tender and then giving the tenderers unreasonable time periods within which to respond. Alternatively, significant areas of the work are unspecified at the time of tender and a provisional sum or, worse still, no allowances at all are made and the employer is ultimately taken by surprise when the final price significantly exceeds the tender sum.

Contracting is not, and never will be, a claims free environment. Claims must be seen to be what they are – fair compensation within the terms of the contract for a situation which is contemplated within the contract alternatively, where not contemplated and where the risk lies other than with the contractor, compensation as the law provides.

1.16.2 Types of Claims

Contractors’ claims fall into three categories; that is contractual, extra-contractual and ex-gratia claims.

Contractual claims: These are claims which can be demonstrated to be due under the contract. The contract will normally require the contractor to serve a written notice with details and substantiation of the claim. The architect/engineer must be satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the claim is admissible under the actual terms of the relevant clause or clauses of the contract before any payment can be made or extension of time awarded.

Extra-contractual claims: These are the claims which although not admissible under the contract, appear to be an obligation to the employer which the courts might uphold in common law. Such an obligation will usually be attributable to the employer’s action or inaction. Common law damages claims should be agreed between the employer and contractor failing which the matter would be referred to arbitration or litigation.

'Ex gratia claims: Bold text Even though there may be no entitlement to damages for a breach of contract or a tortuous act by the employer, contractors sometimes submit claims requesting ex gratia payment. The usual basis of such an application is that the contractor has suffered a substantial loss on the project which cannot be recovered elsewhere; such claims are rarely entertained by employers.

1.16.3 Mitigation of Construction Claims

It is almost now a truism that whatever is done to avoid risks and subsequently claims during the course of project execution, they always arise. If and when claims are inevitable then a concern should be their magnitude and degree of occurrence. Management strategies are needed that could mitigate the occurrence of inevitable claims. Therefore, the following are proposed as some of the possible mitigating factors:

Thus, there should be proper examination and review of the specifications and drawings, ensuring the documents are understandable, unambiguous and consistent. Field personnel should become familiar with the drawings and specifications and the purposes they are intended to serve, since they may be the first to notice any discrepancies.

(b) Tender Award: The choice of a good contractor with an economic and realistic price requires no emphasis.

(c) Adequate Information: With tendering goes the provision of sufficient data and information on which tenders can be based. The aim being to look for a fair price, which shall take care of substantial foreseeable risks and allow tenderers to plan their operations with sufficient flexibility.

(d) Realistic Estimates: Preparation of realistic estimates should be aimed at as no amount of good project management could overcome estimating deficiency. Unreasonable reduction of tender prices before award should be avoided.

(e) Ensure Prompt Action: When a claim situation is discovered it is important for the parties to move quickly. Contractors should notify and make inquiries as soon as possible for instructions, delays, variations, unforeseeable conditions etc. Responsive negotiation to resolve a claim should be entered into before additional costs accrue. Impartial analysis by the parties and contractual reviews are preferable to permitting valuable time to be lost as the supervising officer and contractor argue the merits.

(f) Establish good working relationship: From the very onset it is important to establish good communication and to ensure a sound working relationship. Some of the new standard procedures now encourage a less adversarial approach. Under these contracts an early warning system stimulates early joint consideration of problems with the estimated total cost being agreed before the commencement of the work.

1.16.4 Claims Procedure and Presentation

1.16.4.1 Notification

Good practice in connection with the submission and consideration of contractual claims suggests that the contractor should give to the PM, within the time prescribed in the contract or as soon as possible, his ‘notice of claim’ which should:

- Explain the circumstances giving rise to the claim;

- Explain why the contractor considers the employer to be liable;

- State the clause(s) under which the claim is made.

1.16.4.2 Entitlement

The contractor should, within the time prescribed in the contract or as soon as possible, follow up this ‘notice of claim’ with a detailed ‘submission of claim’ which should contain the following:

- A statement of the contractor’s contractual reasons for believing that the employer is liable for the extra costs with reference to the clauses under which the claim is made.

- A statement of the event giving rise to the claim, including the circumstance (or changes thereof) he could not reasonably have foreseen.

- Copies of all relevant documentation, such as:

- contemporary records substantiating the additional costs as detailed.

- details of his original plans in relation to use of plant, mass haul diagrams involved.

- relevant extracts from tender programme and make-up of major BOQ rates.

- information demonstrating the individual or cumulative effect of site instructions, variation orders and on-costs relating to the claim.

1.16.4.3 Quantification

Once the entitlement to a claim is established, quantification should follow. The quantification should be adequate and accurate. Many claims fail due to there being exaggerated demands for reimbursement.

1.16.4.4 Clarity

A contractor’s claim should be self-explanatory, comprehensive and readily understood by someone not connected with the contract. It should contain a title page, an index, recitals of the contract particulars, relevant clauses and reasons for the claim and an evaluation. These guidance notes would seem to reflect good practice no matter what the project or the conditions of contract.

1.16.4.5 Evaluation of Contractor’s Claims=

(b) Summary of claim

(c) Contractor’s contention of principles (and value when stated)

(d) Analysis of principles of claim

(i) circumstances giving rise to claim

(ii) principles on which the claim is considered (including relevant clauses in the conditions of contract)

(iii) description and justification of claim

(iv) recommendation on principles of claim

(e) Analysis of quantum of claim

(i) analysis of contractor’s justification

(ii) apparent discrepancies

(iii) recommendation for quantifying claim

(f) Appendices

(i) index and copies of correspondence

(ii) tables

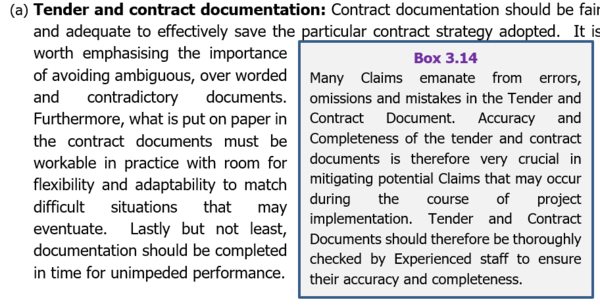

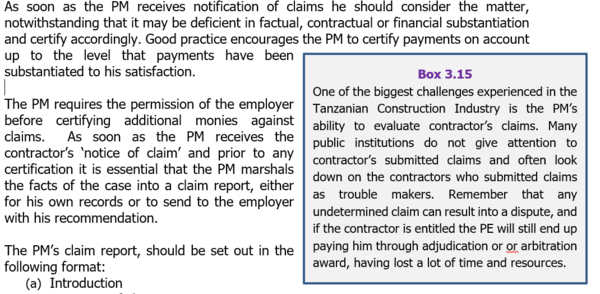

(iii) drawings